MAGYARUL

This is the end, the traveller might say, as the sky widens over the Sulina lighthouse and the river becomes a seemingly endless expanse of water. But is this really the end? According to Plato, "Heraclitus says somewhere that everything is in motion and nothing remains unchanged, and comparing beings to the flow of a river, he says that you cannot step into the same river twice." To find a reassuring answer to the question of where the Danube ends, we need to travel hundreds of kilometres out into the Black Sea, more than a kilometre deep, and over millions of years in time.

|

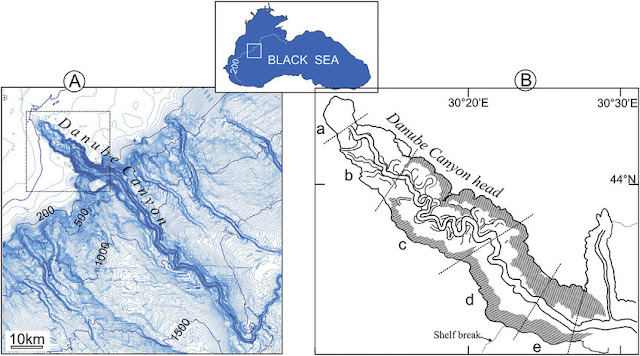

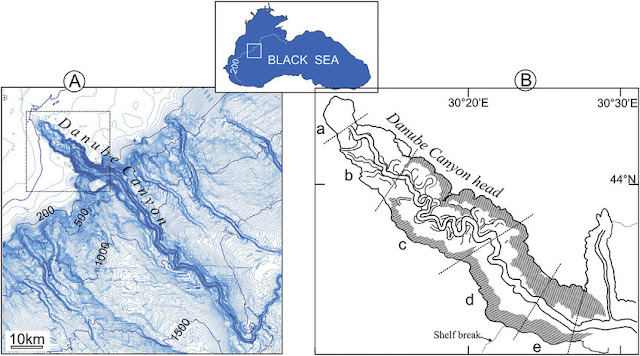

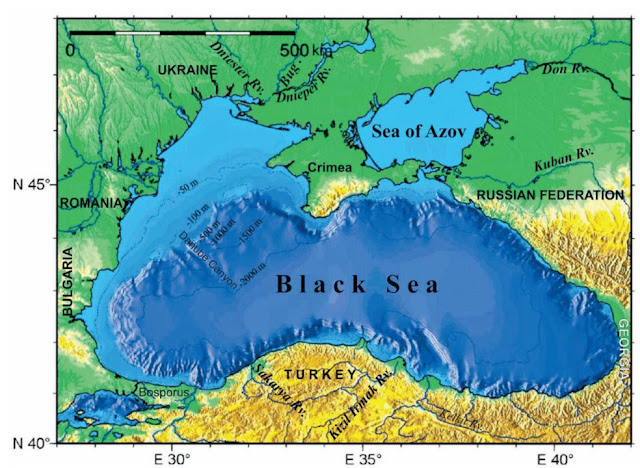

| Fig. 1. The situation of the Danube (Viteaz)-canyon at the bottom of the Black Sea. (source) |

It is necessary to translate the philosophical ideas of Heraclitus into the language of the more specific earth sciences. Since the Danube has existed, its parameters have been constantly changing, as they did in the early tens of millions of years, during the period of natural evolution when it was shaped solely by natural conditions, and later, in the time span of up to 10,000 years, when human influence has been increasing. The length of the river has changed, at first only the small river meandering in the Alpine foothills filling lakes and bays of the Paratethys Sea, the extent of its catchment area has changed, while its upper reaches have often been overtaken by neighbouring watercourses, such as the Rhine. This, together with changes in climate, has led to changes in discharge, for example, melting after the last glaciation significantly increased the discharge, while dry warm periods reduced it. To give specific examples, the Danube filled (with other rivers) the Pannonian lake, while the Rhine conquered a significant catchment to the west, and the increased discharge spread a huge amount and thickness of gravel material over the Hungarian section of the river, and not only has the source of the Danube changed over the millennia, but the estuary, i.e. the delta, has also migrated, and has been further west than it is today, but what is relevant for the present post is that the Danube has been moving from the river basin to the delta: further east.

|

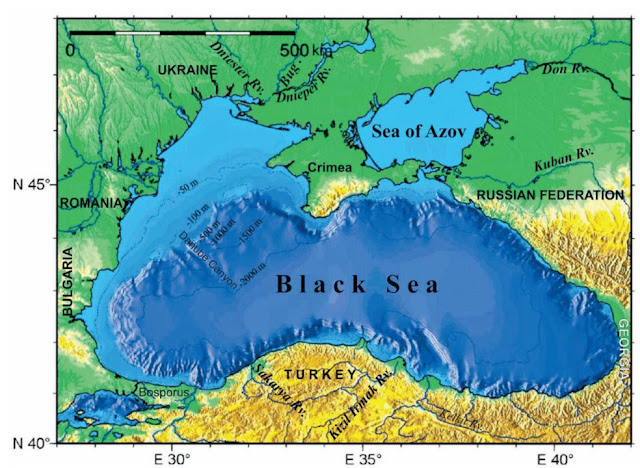

Fig. 2. The position of the Danube canyon on Google maps.

|

A hundred kilometres southeast of the present Danube Delta, deep-sea research has revealed a distinctive, long and deep gorge valley in the depths of the Black Sea (see Figure 2). Its official name suggests that the Danube must have something to do with it. In the north-western basin of the Black Sea, there is a relatively large shallow shelf area of 140*170 kilometres, with depths varying between 20 and 140 metres, into which four major rivers transport their sediment: the Danube, the Dniester, the South Bug and the Dnieper. The head of the canyon valley cuts deep into the rim of the continental shelf and extends down to the level of the deep-sea bed, while no distinct morphological relationship is visible between the present Danube delta and the head of the canyon valley.

|

| Fig. 3. Major tributaries of the Black Sea (the Dniester on the wrong place) and depth contours (source) |

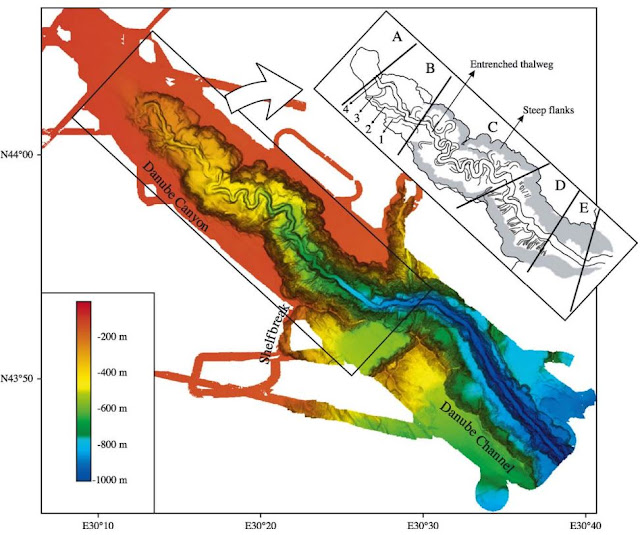

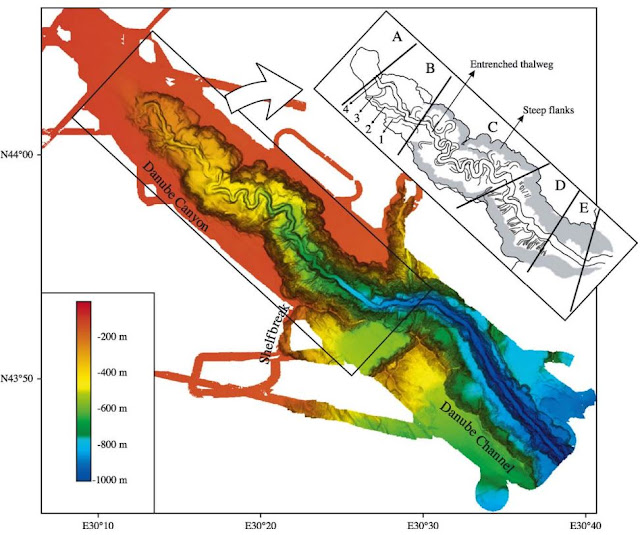

The head of the Danube Canyon, which cuts into the shelf area, begins at a depth of about 90 metres, and its terminus is lost 100 kilometres away on a wide fan-shaped alluvial cone, breaking up into several branches, in the deepest zone of the Black Sea, at the deep-sea floor, at a depth of about 2100 metres. By comparison, the deepest point in the Black Sea is at 2210 metres. The canyon is two kilometres wide on the section that cuts into the backshore, with steep side walls (up to 30°) and shell-shaped notches all around. The V-shaped valley, which cuts into the valley floor at a depth of 400 metres, curves from the north-west to the south-east with a steep descent on the continental slope, where the valley widens to a width of six kilometres. The distinctive valley continues as a channel on the seabed, where it branches off into a deep-sea delta of its own making. This is not a unique phenomenon, as similar deep-sea canyon valleys have been observed in other rivers, whether in the Amazon, Hudson or Congo estuaries. It would be wrong to think that this submarine geomorphology was formed by river water, so it is questionable whether the Danube ends here.

|

Fig. 4. The relief of the Danube Canyon (source)

|

It is also questionable how the Danube could have formed this deep-sea gorge, far to the south-east of its known estuary. Since fresh water cannot continue to flow down to the bottom of the sea, forming erosion trenches, once it reaches the erosion base, some other effect must be behind the phenomenon. First of all, it is worth looking at the specific characteristics of the Black Sea, which in many ways is unique compared to other seas. The Black Sea is a typical inland sea, connected to another inland sea only through a thin strait, the Bosporus, as the Mediterranean Sea is also connected to the Atlantic Ocean through a very narrow strait at Gibraltar. The Bosphorus Strait, which connects the two bodies of water, has a minimum depth of only 36.5 metres at the Golden Horn, which means that if global sea levels fall below this point, the Black Sea becomes a saltwater lake. By the way, the sea is also a unique body of water in terms of salinity, since it is a moderately saline brackish water body at the surface down to a depth of 150 metres. This layer is caused by rivers flowing into the sea with high freshwater discharge and oxygen-rich freshwater, under which there is a saltier, anoxic, lifeless layer of water, and the two layers do not mix. The lack of mixing of fresh and salt water rules out the possibility that the Danube water could be currently shaping this canyon. Nevertheless, it cannot be said that it is an inactive valley.

|

| Fig. 5. The sediment fan of the Danube canyon (source) |

There is another possibility for the formation of the canyon, and that is the drastic lowering of sea level, in other words regression. Sea-level rise and fall in the Black Sea is different from similar movements in the world's oceans because of the aforementioned Bosporus threshold. The last 20,000 years provide a good example to illustrate this; at the time of the last glacial maximum (LGM), the Black Sea was most likely a fresh, or at least reduced salinity lake, which received its water from the rivers flowing into it. Its surface was about 110-120 m below present-day sea level at the time of its maximum advance from the ice sheet (white line in Figure 5), i.e. the northern shelf and the Azov Sea were dry. Water covered only the continental slope and the levels of the deep-sea plain. The three major rivers to the west of the Crimean peninsula, the Dniester, the South Bug and the Dnieper, reached the lake at this time in a common channel, while the mouth of the Danube may have been separate and south-west of it, at the head of the canyon valley. As it was a tidal stagnant water, it cannot be assumed that the Danube had a gorge-like estuary at the end of the Ice Age, and almost certainly had a delta estuary even then, which may raise further questions about its geomorphology.

The water level in the Black Lake started to rise after the end of the LGM. Meltwater from the ice sheet in the north (Scandinavia and NW Russia) significantly increased the discharge, capacity of sediment transport of rivers flowing into the lake. During the same period, the rate of the sea level rise in this basin was greater than in the Mediterranean. 13,000 years ago, the level of the Black Lake was approaching, perhaps even reaching, the lovest level of the Bosporus Strait, while the level of the world's oceans was still 70-80 metres below the present level. Some theorise that the freshwater of the Black Sea may have been tumbling through the Marmara Sea into the Mediterranean at this time. However, the rise of the lake stopped at a certain point and the water level began to fall again as the meltwater supply decreased, the waters from the ice sheet no longer finding their way down the great rivers of the Steppes, but heading for the lake that formed where the Baltic Sea once the ice dam had disappeared. 8000 years ago, the situation was almost restored, the shelf area became dry again, the lake level was -90 to -100 metres below the present level. The dry and cold climate built up dune valleys in the coastal areas from the transported sediment, and the rivers took possession of their pre-transgression bed and estuary.

Around 8,500 years ago, the rising level of the Mediterranean Sea reached and exceeded the Bosporus threshold, and salt water flowed into the Black Lake basin. In an extremely short time, the water level rose by 70-80 metres. Many believe this to be the historical basis of the biblical flood, but it is certain that the former coastal morphology of the Black Sea, the sand dunes, the wave-lashed shores and delta area, were not destroyed by erosion, but were preserved in the deep by the rapid rise in sea level. The Black Sea was thus formed, and its level and the location of the Danube delta were fixed for thousands of years.

|

| Fig. 6. Changes in the Black Sea level since the LGM (source) |

However, it is also important to consider whether the Black Sea level could have been lower at other times, when fluvial erosion would have had the opportunity to exert its erosive effects right down to the bottom of the steep continental slope. Several glaciation phases occurred during the Pleistocene, but global sea level fell to around -120 m in all of them, and as the Black Sea basin was in a similar position during this geological epoch, it is likely that the water level here did not change more than observed in the LGM. If we look at earlier ages, the effects of glaciation can be excluded as a possible cause, but at the end of the Miocene, during the Messinian period (5.9-5.3 million years ago), a tectonic event occurred that caused a series of successive drastic drying events in the Mediterranean basin. During the Messinian Salt Crisis, the connection with the Mediterranean Sea was interrupted and the water balance of the Black Lake turned negative, with evaporation becoming dominant. However, the extent of the sea-level fall is still a matter of debate, with seismic measurements suggesting a subsidence of several hundred metres, while paleontological studies suggest a few tens of metres. However, this regression certainly did not affect the Danube delta, which at that time was still filling the Carpathian Basin and the Pannonian Lake, and the Romanian Plain could have been a (Paratethys) bay (Figure 7).

|

Fig. 7. The Black Sea basin during the Messinian Salt Crisis (source)

|

It follows, therefore, that the Danube canyon, hidden in the depths of the Black Sea, could only have formed towards the end of the Pleistocene, when the Danube delta extended to the edge of the continental shelf in two morphologically distinct phases, during the LGM, almost 13,000 years ago, and it is also likely that the Danube was shaping the canyon, even below sea level. However, slope mass movements, not sweetwater influx, played the main role in the formation of the canyons. The huge amounts of loose sediment transported to the steep rim of the shelf were sometimes unstable and would slide down the slope in landslides, and the lack of material would be replaced by a widening gorge due to the continuing slurry. As the sediment was constantly replenished, the slides recurred, but now at the predicted location and along the slip path. Although submarine slides and gullies can also form in places where there is no estuary, there is no marked backward movement into the continental shelf. The regular mudslides formed a channel on the self-slope and then spread out over the deep-sea plain as gravity ceases, forming a flat alluvial cone. This sediment is known in geology as turbidite, and in many places it can be studied as rock compressed into mountains.

|

| Fig. 9. ábra Undersead turbidity currents. (wikipedia) |

Although sea-level rise and land receding have rendered the gorge valley inactive over time, and human impact (hydrolelectrical dams) has radically reduced the amount of sediment reaching the sea, further landslides may still occur at depth on the steep sides of the gorge. So this is where the Danube ends, at the bottom of the Black Sea, in a geologically very young valley hidden from human sight and its associated deep-sea alluvial cone, hundreds of kilometres from the present-day estuary.

International literature on the canyon is fortunately abundant and can be found here:

- https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=2afea9bb0a2b98713e7ed97b7ff19ff81cffce1f

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-02271-z

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0012825218306998

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277775413_Evolution_of_the_Danube_Deep-Sea_Fan_since_the_last_glacial_maximum_New_insights_into_Black_Sea_water-level_fluctuations

- http://www.blacksea-commission.org/_publ-soe2009.asp

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298354387_Submarine_canyons_of_the_Black_Sea_basin_with_a_focus_on_the_Danube_Canyon

- https://sci-hub.se/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2004.03.003

- https://www.britannica.com/science/submarine-canyon

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0012821X12006565

- https://sci-hub.se/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2012.11.038

- https://sci-hub.se/10.1144/petgeo2015-093

- https://geoecomar.ro/beta/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/02_OLARIU_c1_2020.pdf

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0921818108001744

- https://books.google.hu/books?id=0iXMJJQblg0C&pg=PA82&hl=hu&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=1#v=onepage&q=canyon&f=false

- https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2016EGUGA..1811391C/abstract

- https://journals.openedition.org/mediterranee/8186